Calibration curve

In analytical chemistry, a calibration curve is a general method for determining the concentration of a substance in an unknown sample by comparing the unknown to a set of standard samples of known concentration.[1] A calibration curve is one approach to the problem of instrument calibration; other approaches may mix the standard into the unknown, giving an internal standard.

The calibration curve is a plot of how the instrumental response, the so-called analytical signal, changes with the concentration of the analyte (the substance to be measured). The operator prepares a series of standards across a range of concentrations near the expected concentration of analyte in the unknown. The concentrations of the standards must lie within the working range of the technique (instrumentation) they are using (see figure).[2] Analyzing each of these standards using the chosen technique will produce a series of measurements. For most analyses a plot of instrument response vs. analyte concentration will show a linear relationship. The operator can measure the response of the unknown and, using the calibration curve, can interpolate to find the concentration of analyte.

In more general use, a calibration curve is a curve or table for a measuring instrument which measures some parameter indirectly, giving values for the desired quantity as a function of values of sensor output. For example, a calibration curve can be made for a particular pressure transducer to determine applied pressure from transducer output (a voltage)[3]. Such a curve is typically used when an instrument uses a sensor whose calibration varies from one sample to another, or changes with time or use; if sensor output is consistent the instrument would be marked directly in terms of the measured unit.

The data - the concentrations of the analyte and the instrument response for each standard - can be fit to a straight line, using linear regression analysis. This yields a model described by the equation y = mx + y0, where y is the instrument response, m represents the sensitivity, and y0 is a constant that describes the background. The analyte concentration (x) of unknown samples may be calculated from this equation.

Many different variables can be used as the analytical signal. For instance, chromium (III) might be measured using a chemiluminescence method, in an instrument that contains a photomultiplier tube (PMT) as the detector. The detector converts the light produced by the sample into a voltage, which increases with intensity of light. The amount of light measured is the analytical signal.

Most analytical techniques use a calibration curve. There are a number of advantages to this approach. First, the calibration curve provides a reliable way to calculate the uncertainty of the concentration calculated from the calibration curve (using the statistics of the least squares line fit to the data). [4]

Second, the calibration curve provides data on an empirical relationship. The mechanism for the instrument's response to the analyte may be predicted or understood according to some theoretical model, but most such models have limited value for real samples. (Instrumental response is usually highly dependent on the condition of the analyte, solvents used and impurities it may contain; it could also be affected by external factors such as pressure and temperature.)

Many theoretical relationships, such as fluorescence, require the determination of an instrumental constant anyway, by analysis of one or more reference standards; a calibration curve is a convenient extension of this approach. The calibration curve for a particular analyte in a particular (type of) sample provides the empirical relationship needed for those particular measurements.

The chief disadvantages are (1) that the standards require a supply of the analyte material, preferably of high purity and in known concentration, and (2) that the standards and the unknown are in the same matrix. Some analytes - e.g., particular proteins - are extremely difficult to obtain pure in sufficient quantity. Other analytes are often in complex matrices, e.g., heavy metals in pond water. In this case, the matrix may interfere with or attenuate the signal of the analyte. Therefore a comparison between the standards (which contain no interfering compounds) and the unknown is not possible. The method of standard addition is a way to handle such a situation.

Contents |

Error in calibration curve results

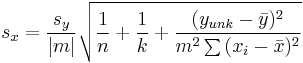

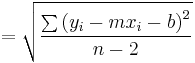

As expected, the concentration of the unknown will have some error which can be calculated from the formula below.[5][6] This formula assumes that a linear relationship is observed for all the standards. It is important to note that the error in the concentration will be minimal if the signal from the unknown lies in the middle of the signals of all the standards (the term  goes to zero if

goes to zero if  )

)

is the standard deviation in the residuals

is the standard deviation in the residuals

is the slope of the line

is the slope of the line is the y-intercept of the line

is the y-intercept of the line is the number standards

is the number standards is the number of replicate unknowns

is the number of replicate unknowns is the measurement of the unknown

is the measurement of the unknown is the average measurement of the standards

is the average measurement of the standards are the concentrations of the standards

are the concentrations of the standards is the average concentration of the standards

is the average concentration of the standards

Applications

- Analysis of concentration

- Verifying the proper functioning of an analytical instrument or a sensor device such as an ion selective electrode

- Determining the basic effects of a control treatment (such as a dose-survival curve in clonogenic assay)

Notes

- ^ http://terpconnect.umd.edu/~toh/models/CalibrationCurve.html

- ^ http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM070107.pdf

- ^ ASTM: Static Calibration of Electronic Transducer-Based Pressure Measurement Systems Example of calibration curve for instrumentation.

- ^ The details for this procedure may be found in D. A. Skoog et al. (2006). Principles of Instrumental Analysis., as well as many other textbooks.

- ^ http://www.chem.utoronto.ca/coursenotes/analsci/StatsTutorial/ConcCalib.html

- ^ http://alpha.chem.umb.edu/chemistry/ch361/Salter%20jchem%20ed%201.pdf

Bibliography

- Harris, Daniel Charles (2003). Quantitative chemical analysis. San Francisco: W.H. Freeman. ISBN 0-7167-4464-3.

- Skoog, Douglas A.; Holler, F. James; Crouch, Stanley R.; (2007). Principles of Instrumental Analysis. Pacific Grove: Brooks Cole. pp. 1039. ISBN 0-495-01201-7.

- Lavagnini I, Magno F (2007). "A statistical overview on univariate calibration, inverse regression, and detection limits: Application to gas chromatography/mass spectrometry technique". Mass spectrometry reviews 26 (1): 1–18. doi:10.1002/mas.20100. PMID 16788893.

|

|||||||||||||||||